Deaf Havana Scrapped An Entire Album To Find Their True Voice On ‘We’re Never Getting Out’

Fifteen years in, British alt-rockers Deaf Havana are still rewriting their own rulebook. With their forthcoming seventh album, We’re Never Getting Out (out this Friday 3rd October via So Recordings & Civilians), frontman James Veck-Gilodi steers the band into its most personal territory yet – a record born from scrapping an entire finished album, starting fresh with close friends, and rediscovering why he makes music in the first place.

Music Feeds spoke to James about rebuilding his creative process, enlisting old mates from The 1975 and Lewis Capaldi’s band, and how writing these songs helped him face down some of his biggest personal battles.

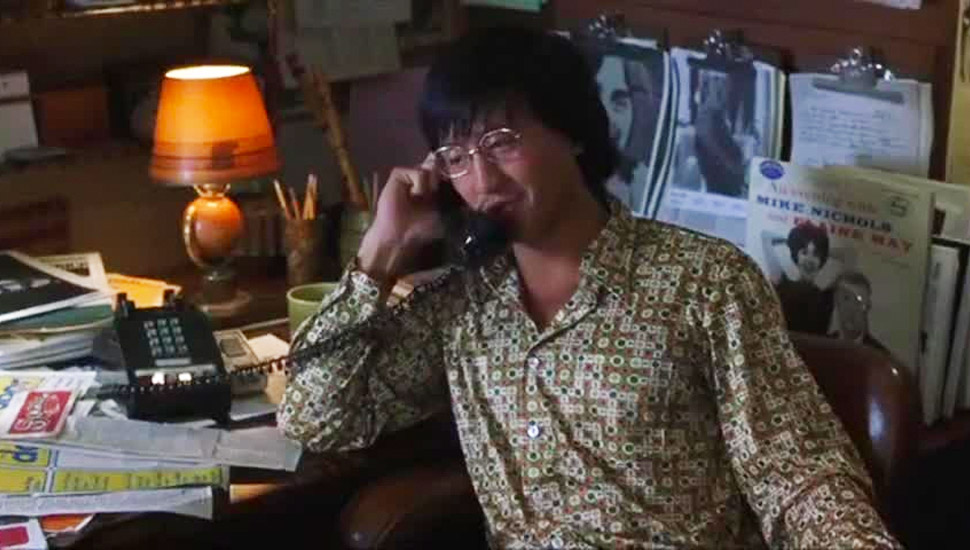

Deaf Havana – ‘Tracing Lines’

Music Feeds: We’re Never Getting Out is your seventh album. Could you tell us the story behind it and the creative process it took for the new record to come together?

James Veck-Gilodi : It took ages because we wrote a record before this one which we thought was going to be the album. We recorded it and then I was like, “this is not good enough to release.” So we scrapped it and started again. We got a new producer, which was my friend George Glue who was living with me at the time, we started writing and he and I would just set a few days a week aside to just write songs. This was the first record where most of the songs were co-written. It didn’t feel like it was co-written because he’s one of my best mates and he and I do a lot of work for other people together. But a lot of it was written in my old house in London, just me, George and Matty. And honestly the actual finished product came together pretty quickly but there was just so much faffing around beforehand because we did a whole record that we thought we were going to release.

But the creative process was great, we managed to get some cool people to play on it as officially it’s only me and my brother in the band, so we get our mates to play live for us. But on the record I got my friend Freddy Sheed who plays for Lewis Capaldi. He used to be in The Japanese House and has played for The 1975. I got him to play drums because the way he plays is so weird. He doesn’t use muscle memory so every single take he does is completely different. So what you hear on that record is the only time he ever played it like that, which is awesome. And then my friend Ross (McDonald) who is in the 1975, he played bass. We were lucky to get some cool people to come and play on it.

MF: Did anything from that unreleased album inform or inspire what you ended up later releasing?

James: There’s two songs which made it over from the previous album but they’re completely different. So there’s a song called Cigarettes and Hotel Beds which is on the album which was on the other album we scrapped and then a song called Hurts to be Lonely, that we changed and put on this one. But other than that, no. It really sounds, even with those songs, like a completely different band.

What we had written and recorded didn’t sound like me. I didn’t feel any connection with it whereas the one we have now, I’m like, “this is the best thing I’ve ever done.” I think the problem was that I just didn’t care. I gave up control and my brother is a fantastic songwriter but it’s not necessarily what I would write. So he and the producer did a lot of the work and I just kind of was honestly getting drunk and not caring. And then I realised, and I was like, “you’re an idiot”. I just wasted so much time and money. It just sounded like I just wasn’t being present enough.

MF: How did starting fresh help you achieve what you wanted to get out of this record?

James: I think it was just the fact that we could start fresh. On the one we scrapped, I hardly wrote any of the lyrics, which is weird because I normally write all the lyrics as the person who sings them. So immediately I was taking away my own connection with the songs. So I just basically was like, “it’s time to pull your finger out and actually do some work.”

It sounds cheesy, but I threw my whole heart and soul into it. I don’t think I realised how personal some of the songs on it are until I listened to it back.

MF: You mentioned before having Ross McDonald and Freddy Sheed play on the record. How did their involvement come to be and what was their influence on the overall sound of the record? Did you write with them in mind, being on the record?

James: No, we didn’t write anything with them in mind, because I didn’t even think about it until we’d written all the songs. And then I thought, we don’t need to get any specific people on this record. They were the first two people I thought of because I’ve been really good mates with both of them for like 10 years, so I just texted them, “By any chance, would you guys be up for this?” And they both said, “yeah.”

In terms of the sound, Ross is a really tasteful bass player. So I knew that he’d just know exactly what to do where, which I don’t. When I play bass, I just play it like a guitar. Sometimes it’s good, but a lot of the time, it just sounds like I’m overplaying. So I knew he’d fix that problem.

But then Freddy is the weirdest. He’s a jazz drummer, even though he’s mainly played in pop bands, he’s like a proper jazzer. And he plays in such a weird way. He didn’t learn the songs from my computer drums. I just said to him, “just play whatever you think would suit the song.” So there’s so much weird stuff, and it’s really hard to replicate live. Our live drummer, Luke, might be the best drummer I’ve ever seen in my entire life, but he plays the opposite to Freddy. He plays really technically and he’s amazing. But Freddy is just so weird. Some of the stuff he does on the album just makes moments on the record which wouldn’t have otherwise been there.

MF: You mentioned how personal the record got for you. How did writing these songs help you process some of your experiences?

James: Well, it got me out of the relationship that I was in. I was writing whilst I was still in the relationship. It definitely gave me some sort of clarity of what to do I think, so it helped in that sense. But I also think there was a lot of stuff in it that I didn’t really process while I was writing or recording it. It mainly happened when I listened to it back. It definitely shone a light on a lot of things I needed to change in my life. And I’ve actually implemented quite a lot of that, which is pretty good.

MF: So now that the album is finished, do you feel more at peace with yourself?

James: I mean, it’s a daily thing. There’s so much stuff I’ve had to work on daily. I’ve quit drugs and alcohol, which I’ve been trying to do honestly for five years and I’ve never been able to, but this time really feels different. I still struggle a lot, like I’m quite negative mentally and I just tend to think the worst. So I’m trying to not be like that, but it’s hard. I’m definitely in the best place I’ve ever been health wise and mentally.

MF: What’s the track from the record that you’d recommend for a new listener to start with? Is there a song that you think introduces listeners to Deaf Havana the best?

James: Probably Tracing Lines. It’s the second to last song. I think it sounds enough like our previous stuff so it’s not going to be like a million miles away from what we’ve already released if people listen to that first. That one is sad, but it’s also got like a little glimmer of hope in it. It’s got a good spread of new and old.

MF: So you’ve spoken about stepping away from making music to just to please others. How has that changed your approach to Deaf Havana?

James: Definitely makes me enjoy it more because I now know that when you try and write stuff for other people, it’s never going to benefit you. There’s been times where I’ve done that. I’ve written music that I think other people want to hear and recorded it. And then six months later, I hate it and don’t want to play it live. And it just doesn’t keep me interested. Whereas these songs are like a piece of me, which sounds cheesy as fuck, but it’s true. So I know that I’m going to enjoy playing them live forever. And I know that they’re not going to lose their meaning because it is a real meaning. It’s not just me trying to make younger people like our band or something, you know?

MF: What do you get out of creating music for yourself? What fills your cup so to speak?

I think I feel like it’s kind of therapeutic for me because I find it easy to express myself that way.

I know that sounds cheesy and cliche. But also I just enjoy it. Like, I feel comfortable doing it because I know I can. Not in an arrogant way, but I can. I feel like that’s what I’m supposed to be doing. So for me, it definitely gives me something that nothing else can. I also love the idea that a stupid thing that you came up with on a guitar in your room can turn into a massive song and can connect with other people. I love that, I still think there’s magic in that. I try to remind myself of that because I definitely forget it, I definitely take it for granted a lot.

MF: If you could go back and give 2008 Death Havana some advice about navigating the music industry and your own expectations, what would it be?

I mean, there’d be some advice towards some shit songs that we’ve released. I definitely would say go back and work on that a little bit and take other people’s criticism instead of getting defensive. But the main thing I would say is don’t get annoyed if stuff doesn’t go exactly the way you think it’s going to go and don’t get too ahead of yourself. Because – this wasn’t in 2008, it was in 2012 – but when we were writing our second record, I genuinely believed that we were going to be massive. And that hurt me a lot because we didn’t get massive. We did fairly well off it, more than I ever really thought. But in my head, I was like, “we’re going to be like Rolling Stones.” So I would say probably don’t let arrogance get ahead of you because that is very detrimental and a bad personality trait. You get a taste of something like that. And then it’s a really rough landing if it doesn’t work out. It is good, because now, [my ego has] been beat down so much that I don’t think I’ll ever get like that again. Because I know what it does to you.

MF: So you’re much more receptive to feedback these days?

100%. That’s also probably just age and experience thing because now I know that my opinion definitely isn’t the best one in the room. And you need other people’s input to create something great.

MF: Finally, what’s on your playlist at the moment? What’s been your favorite musical discovery of 2025, if you’ve got one?

In terms of artist discovery, it’s probably a guy called Medium Build, and a girl called Ethel Cain.

They’re probably the two that I’ve been like, “they’re outstanding.” And I still listen to them every day. They’re the two main artists that I’ve discovered recently that’s hit me. But I’m gonna be honest, I’m bad at this. I don’t listen to that much music, which is going back to the magic thing. I take it for granted. Because when I do find something that I love, it really hits me.

Further Reading

Zebrahead Share Their Fave Soundwave Memories Ahead Of 2025 Aussie Return

The Hives Share Their Favourite Moments Making Their New Album

Love Letter To A Record: Rise Against On Fugazi’s ’13 Songs’

Link to the source article – https://musicfeeds.com.au/features/deaf-havana-scrapped-an-entire-album-to-find-their-true-voice-on-were-never-getting-out/

-

Fojill Full Size Electric Bass Guitar with Rechargeable Battery Bluetooth 10 Watt Amp 4 String Right Handed Beginner Kit Set Package Combo Bundle with Gig Bag and Accessories (Blue)$199,99 Buy product

-

PreSonus Studio 26c 2×4, 192 kHz, USB Audio Interface with Studio One Artist and Ableton Live Lite DAW Recording Software$0,00 Buy product

-

22.5″ Ukulele with Electronic Tuner, Strap, Picks, Carrying Case & Songbook$49,95 Buy product

-

iECO Soprano Ukulele Beginner Kit for Kids Adults 21 Inch Ukelele w/Case Strap Tuner Strings Picks (Blue)$45,99 Buy product

-

Keyboard Piano, Eastar 61 Key Keyboard for Beginners/Professional, Full Size Electric Piano, Classic Wooden Digital Keyboard with Sustain Pedal & Music Stand, Supports MP3/USB/Audio/Mic/Headphones$214,99 Buy product

-

Lindo Sahara Electro Acoustic Bass Guitar (Short Scale 30″) | Nautical Star 12th Fret Inlay – Graphic Art Finish$919,00 Buy product

Responses