Duplicate Works, Diverted Royalties, and What the MLC Isn’t Catching

Image by Mohamad Hassan

The first in a multi-part investigation into how duplicate registrations, orphan ISRC policies, and manual-only dispute handling may be quietly diverting royalties inside the MLC system.

How much royalty income is quietly being diverted to the wrong people? I didn’t realize how deep the issue ran until I got a call from Travis Rosenblatt of Meddling, an A&R platform that, through direct partnerships with DSPs, identified several suspicious cases within the MLC. Travis recently created a database to track these cases.

The Mechanical Licensing Collective was established to streamline digital mechanical royalty payouts. It is an important initiative, and one that many in the industry, including us, want to see succeed. But even well-intentioned systems can be designed in ways that introduce new risks.

That includes the lack of recourse for rights holders and the roll-up of unmatched royalties based on market share, which structurally advantages larger publishers. But the biggest issue is the ease with which the system can be manipulated. There seem to be no effective filters, flags, or alerts in place to identify conflicts or questionable claims when they are submitted.

For rightsholders, there are almost no reliable ways to detect or recover missing royalties. If fraud occurs, you are expected to uncover it yourself, often long after the fact, with little chance of repayment. Major publishers and distributors have the leverage and staff to protect themselves, but unsigned writers, independent publishers, and rights owners are left exposed. The MLC publishes “orphaned” ISRC lists that effectively serve as shopping guides for fraudsters, while loopholes in distribution platforms make it easy to hijack legitimate works. The result is a system where honest actors carry the burden and opportunists exploit the gaps unchecked.

A Bruno Mars Track With Conflicting Claims

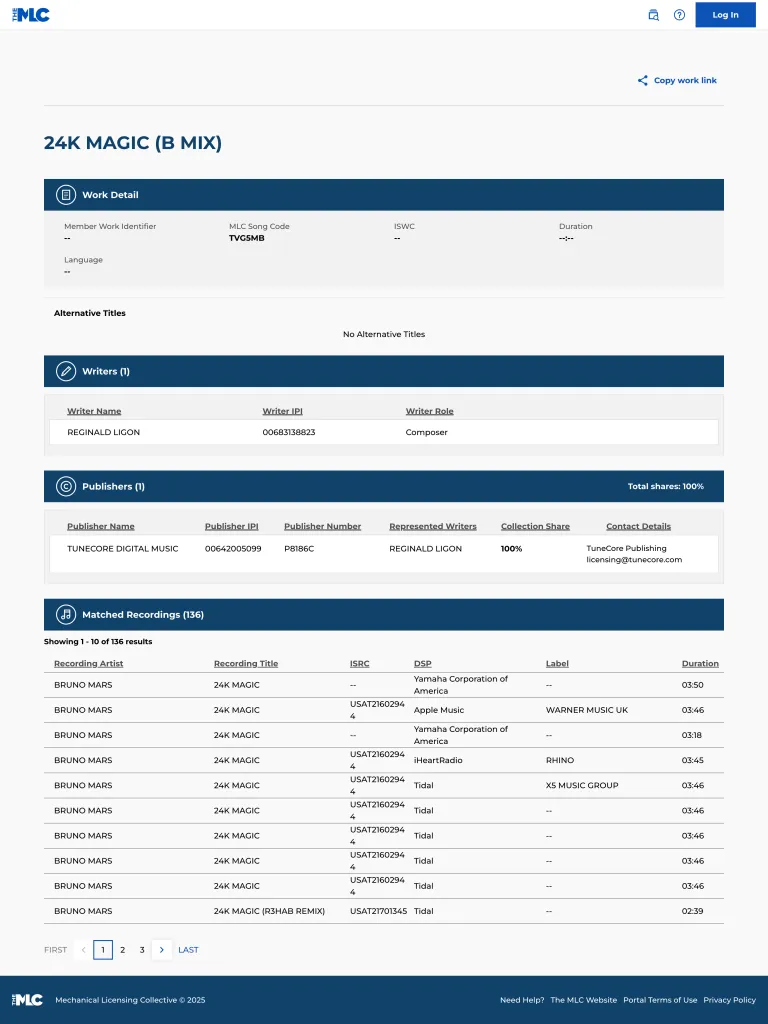

The example that was initially brought to my attention involves the track “24K Magic” by Bruno Mars. Two separate works appeared in the MLC’s database using the same ISRC. Below, you will see the work that was siphoning off royalties from the Mars song. Note: this has been removed from MLC, seemingly as a result of my investigation.

The removed work

The conflicting work was titled “24K Magic (B Mix)”, credited solely to Reginald Ligon, and published by TuneCore Digital Music (see the image above, as the work has been removed from MLC).

It claimed 100 percent ownership of over 100 ISRCs and was matched to more than a dozen DSPs, including Apple Music, Tidal, and iHeartRadio.

The correct registration is here.

I discovered this issue and reported it to TuneCore, the MLC, and the affected publishers, including BMG. BMG confirmed the error to the MLC, which resulted in the removal of the ‘B Mix’ version from the database. PRS for Music confirmed the issue never appeared in their system.

BMI confirmed that “24K Magic (Mix B)” was an unauthorized remix. The account was flagged in March 2024, and payments were stopped with minimal domestic payout impact per the PRO. They issued the following statement:

“24K Magic (Mix B)” was registered with BMI, and in March 2024, it was identified as an unauthorized remix. At that point, the account was immediately flagged for investigation, and payments stopped. The overall impact, including the domestic payout, was very minimal. BMI has a dedicated team that monitors hundreds of thousands of songs submitted each year for improper registrations and fraud. If a discrepancy is detected, we promptly put a hold on the account, conduct a thorough investigation, and remove the work should it be confirmed as a fraudulent registration”.

BMI’s approach appears to be proactive, as they stopped payments over a full year before I manually flagged the work to MLC, the Mars song’s publishers, and TuneCore.

SOCAN, Canada’s largest performing rights organization, also confirmed the song was in its system, but they had not paid out any royalties on it. They stated, per their counsel, Fraser Turnbull:

“The song that you noted is in SOCAN’s system, but we have not paid out any royalties on it. Suspicious registrations like this are very concerning, and we have been strengthening fraud detection practices to identify them.”

I am unsure whether the fraud was prevented through detection measures in SOCAN, or if the non-payment to a fraudster can be attributed solely to slower payment cycles, which allow for more time for due diligence. Regardless, not paying fraudsters is a win.

The MLC left the fraudulent work active until an outside party (me) reported it. They made payments to the fraudster and have not demonstrated system-wide safeguards to prevent similar abuse, including additional ones from Reginald Ligon.

The MLC characterized the amount of diverted royalties as “very small.” But when hundreds of millions are distributed, even a fraction of a percent could represent millions of dollars. For individual rights holders, any diversion can be significant.

I kept digging, and the more I looked, the more I found. Ligon has other questionable works still active, including:

- “Unforgettable (B Mix)” by French Montana

- “Havana (B Mix)” by Camila Cabello

- “The Shape of You (possible future target? No ISRC matches yet)

- “Love You Better” (Ty Dollar Sign)

If removing “24K Magic (B Mix)” was justified, why do these others remain? The lack of follow-up indicates that the MLC is not implementing effective anti-fraud practices before registrations or taking the necessary steps to prevent known fraudsters from continuing to steal from rightful owners. The MLC has not communicated a plan that would catch repeat abuse.

Another Fraud Pattern

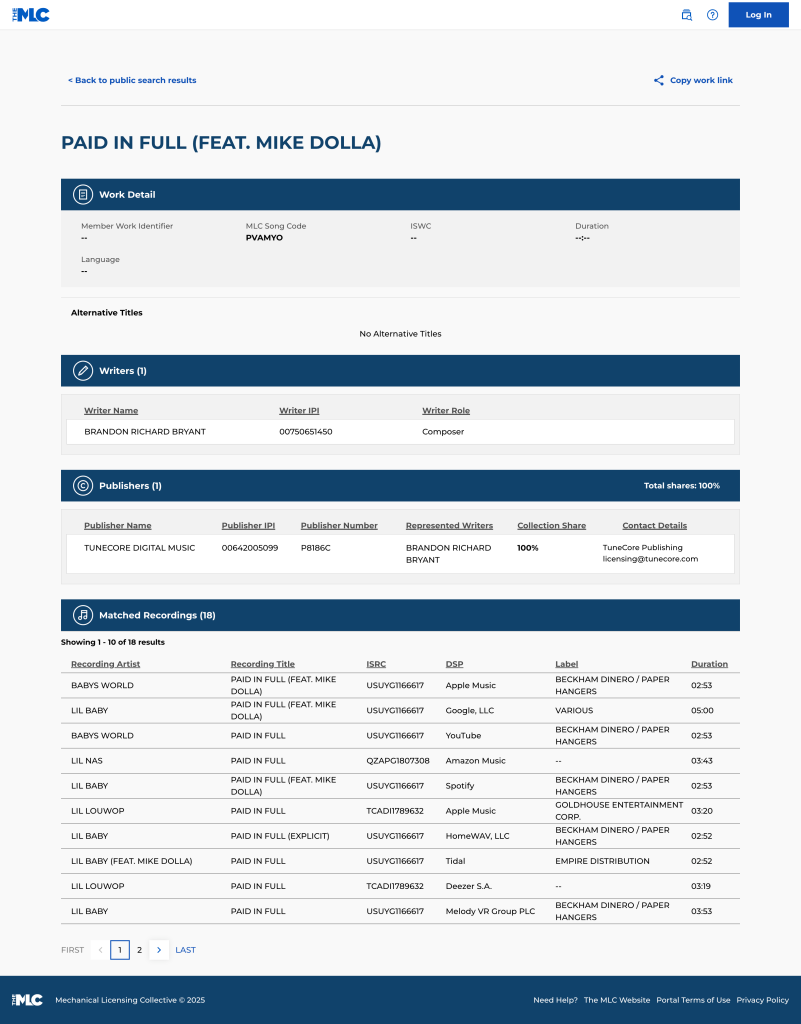

Ligon is far from alone. Another TuneCore-registered writer, Brandon Richard Bryant (IPI: 00750651450), appears, based on MLC portal data, to be exploiting the same flaw. He is listed as the composer on more than a dozen commercial recordings in the MLC database, including:

- “Tied In (Connected)” by Lil Baby

- “WITHTE BAG” by Lil Baby

- “Hustle” by Lil Baby

- “Paid in Full” by Lil Baby

- “Real Shit” by Lil Baby

And much more below:

Many (including the example below) are registered with 100 percent ownership, despite these works already being registered and attributed to one or more legitimate writers. These works are matched to active recordings on major DSPs. There is no indication that they have been reviewed, challenged, or removed. No audit trail, no notice of conflict, no payout reporting.

“Paid In Full” takes on a new meaning.

I can’t help but wonder, if someone like Rosenblatt can detect these patterns, why can’t the MLC or TuneCore?

The MLC’s KYC Reality

The MLC collects some identifying information when onboarding members, but these measures fall far short of full Know Your Customer (KYC) or Know Your Business (KYB) protocols in regulated finance and other established sectors. There is no evidence of account freezes, broader risk reviews, or system-wide audits following credible fraud reports.

In financial systems, the Bank Secrecy Act and USA PATRIOT Act require verifying identities, maintaining verification records, screening against watchlists, and having anti-money laundering programs. A fraud report triggers an immediate review and often an account freeze.

The MLC handles hundreds of millions of dollars per year. TuneCore is the publisher of record for many of the questionable works in this investigation. Yet neither has enforced KYC in a way that stops abuse or repeat abusers.

We know this isn’t an impossible task. YouTube’s Content ID has handled ownership disputes and associated royalty distributions for years. When claims exceed 100%, YouTube freezes payouts and holds the money until the issue is resolved. If two companies both claim too much, the system doesn’t simply pay both of them. It waits. Someone picks up the phone, adjusts their share, and the royalties start flowing again. Simple fix. I’m not suggesting Content ID is perfect. This is an issue they have solved, and MLC and others can emulate what is known to work.

Here’s the bottom line: The MLC has admitted that royalty diversion does occur in these cases, and that it occurred in the case of ‘24k Magic’.

The MLC confirmed royalties were diverted in the Bruno Mars case, but has not disclosed how many other cases exist, which works were involved, or what steps were taken to address losses. The MLC spokesperson informed me that a process exists for ‘crediting and debiting’ in such cases. However, if Ligon received $1 million from a fraudulent source, how can he be compelled to repay?

A Case Study: One ISRC, Two Listings

Jeff Price, founder of Audiam and former CEO of TuneCore, provided another example. “The Most Fashionable Faction (feat. Harry Callaghan)” by The Stupendium shares the same ISRC (QZMER203256) across two separate MLC entries with slightly different metadata. One version includes the songwriter’s name and is matched to a work. The other omits the songwriter, remains unmatched, and does not pay royalties.

Because the MLC treats them as separate recordings, royalties from the unmatched version are never paid unless the problem is found and manually corrected. This is not an anomaly. It is how the system operates.

More to Come

This is just the start; the MLC isn’t the only platform being targeted by fraudsters, and it isn’t the only one failing to stop these scams. But it’s certainly a problematic platform: Rosenblatt has already cataloged more than 400 suspicious works, and that might be scratching the surface.

Unfortunately, this is a problem whose roots go deeper than bad processes and tracking misses. According to many who agreed to speak with DMN, many of these issues date back to the formation of the MLC itself, and the complex politics and dealmaking that shaped its creation. It’s a murky history we’ll be delving into over the coming months.

For now, if you are a songwriter, publisher, or catalog owner, you should be actively monitoring the database. You might already be losing money without realizing it.

Link to the source article – https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2025/09/03/mlc-duplicate-works-royalty-fraud/

-

Novation Launchpad X Grid Controller for Ableton Live$142,99 Buy product

-

Asmuse 5 String Banjo, Full Size Banjo with 24 Brackets, Banjo Beginner Kit with Bag Tuner Strap Strings Pickup$146,99 Buy product

-

Donner DED-200 Electric Drum Sets with Quiet Mesh Drum Pads, 2 Cymbals w/Choke, 31 Kits and 450+ Sounds, Throne, Headphones, Sticks, USB MIDI, Melodics Lessons (5 Pads, 3 Cymbals)$379,99 Buy product

-

Adam Audio T5V Studio Monitor (Pair) with Professional Grade XLR Cables, Stereo Interconnect Cables and StreamEye Polishing Cloth$299,99 Buy product

-

Sai Musical Cornet Trumpet Bb Flat Orange Nickel, Hard Case, Mouthpiece – Ideal for All Skill Levels: Beginner, Student, Professional$119,00 Buy product

-

PreSonus Revelator io44 USB-C Audio Interface for music production and streaming with built-in mixer and easy-to-use effects presets plus Studio One DAW Recording Software$0,00 Buy product

Responses