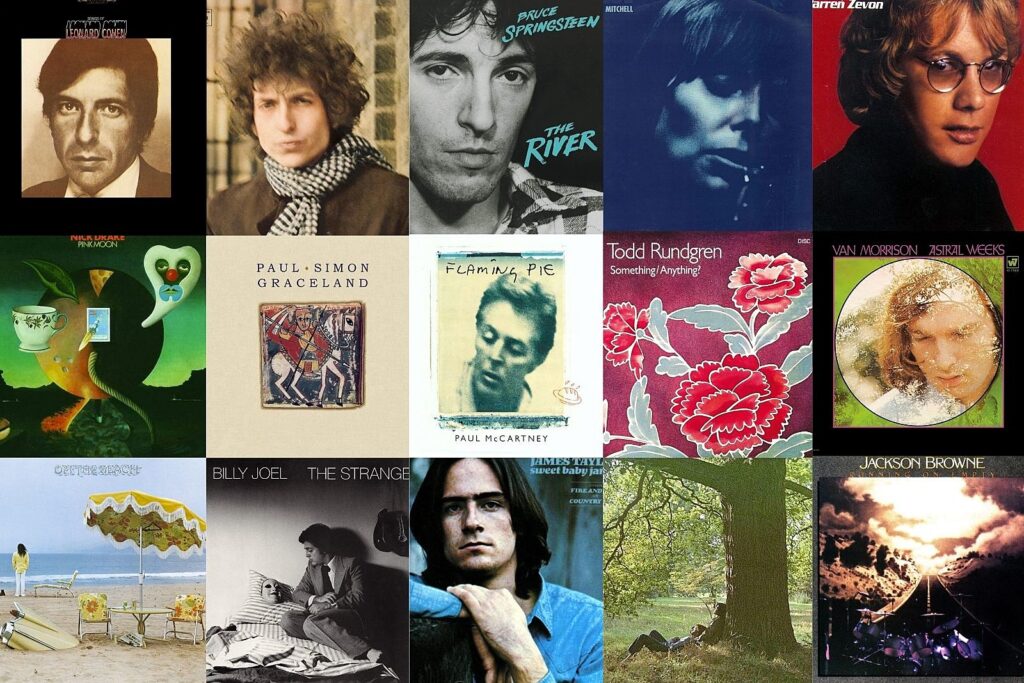

Uncut’s 50 best singer-songwriter albums

Back in Take 199 [December 2013 issue], the Uncut team took on the emotional task of compiling a Top 50 of the most powerful, confessional singer-songwriter albums. From Tim Hardin 1 to Once I Was An Eagle (in chronological order, that is)… are you ready to be heartbroken?

Back in Take 199 [December 2013 issue], the Uncut team took on the emotional task of compiling a Top 50 of the most powerful, confessional singer-songwriter albums. From Tim Hardin 1 to Once I Was An Eagle (in chronological order, that is)… are you ready to be heartbroken?

1 Tim Hardin

Tim Hardin 1

(Verve Forecast, 1966)

Either courageously or compulsively, the gifted but tormented Hardin held up a mirror to his psyche in a series of revealing songs on his first album. “Reason To Believe”, “How Can We Hang On To A Dream?” and “Misty Roses”, addressed to Susan Morss, the muse of many of his best songs, expose Hardin’s startling vulnerability. In “Reason…”, he confronts her, shattered by alleged betrayal (“Knowing that you lied, straight-faced while I cried”) before admitting he still “look[s] to find a reason to believe” in the romantic ideal she’s ruined for him. And lurking behind the near-whispered tenderness of “Misty Roses” is a suffocating possessiveness (“Too soft to touch/But too lovely to leave alone”).

2 Leonard Cohen

Songs Of Leonard Cohen

(Columbia, 1967)

A key album for any singer-songwriter intent on turning real life experiences into song, Cohen’s debut is scattered with names, places and events explicitly drawn from his first 33 years. “Suzanne” recalls his ritualistic – and platonic – meetings in Montreal with Suzanne Verdal, while the titular woman of “So Long, Marianne” is Marianne Jensen, his lover and muse for much of the ’60s. “Sisters Of Mercy”, which dramatises a night spent with two women in an Edmonton hotel room, is the first of countless Cohen songs seeking spiritual salvation from a sensual encounter. His songs turned inward to much darker effect on Songs Of Love And Hate, but his debut album set the standard.

3 Laura Nyro

New York Tendaberry

(Columbia, 1969)

Nyro’s previous album, Eli And The Thirteenth Confession, provided rich pickings for other artists looking for hit singles (The 5th Dimension’s “Stoned Soul Picnic”, Three Dog Night’s “Eli’s Coming”) but there weren’t as many takers for this starker, more personal set. A devastating account of emotional turmoil, the album reflects her own experiences in New York. “You Don’t Love Me When I Cry”, “The Man Who Sends Me Home” and “Sweet Lovin’ Baby” are first-person confessionals. In other songs, the New York streets, buildings and people provide a backdrop to her innermost thoughts (“Gibsom Street”, “Mercy On Broadway”, the latter sampling the sound of gunfire).

4 Al Stewart

Love Chronicles

(CBS, 1969)

Stewart’s second album is often name-checked as the first time the word “fuck” appeared in a pop song, and is also notable for the calibre of its session players (Jimmy Page, Richard Thompson and others from Fairport Convention). The centrepiece, though, is the 18-minute title track, a frequently uncomfortable autobiography in which he catalogues the highs and lows of his romantic endeavours; losing his virginity in a Bournemouth park, encounters with groupies, searching for ’60s permissiveness (“beer cans and parties, debs and arties…”), bouts of self-loathing, and ultimately finding true love in the last three verses. “You Should Have Listened To Al” picks over the bones of another doomed affair, but in a lighter, wittier tone (“she left me the keys and a dozen LPs”).

5 Dory Previn

On My Way To Where

(Mediarts/United Artists, 1970)

Dory Previn had more cause for confession than most. Raised in a strict Roman Catholic household by an alcoholic mother and violent father, the collapse of her marriage to composer-conductor André Previn led to mental breakdown, electro-shock therapy and an intensive bout of self-analysis. All of which provided the raw ammunition for solo debut, On My Way To Where. The most striking song was “Beware Of Young Girls”, a fragrant lullaby with lyrics that served as a bitter swipe at actress Mia Farrow, with whom her husband had begun an affair two years previously. Meanwhile, “With My Daddy In The Attic” and “I Ain’t His Child” were disturbing pieces of barely veiled autobiography.

6 John Lennon

John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band

(Apple, 1970)

Unburdened by the break-up of The Beatles and emboldened by his Primal Scream sessions with Dr Arthur Janov, Lennon didn’t so much release as unleash his first solo album on an initially shocked world. Armchair shrinks had a field day with the Oedipal undercurrents of “Mother”, the sense of betrayal animating “I Found Out” and “Working Class Hero”, the existential despair of “Isolation” and the renunciations in “God”. Throughout this unprecedented outpouring, the abandon of Lennon’s singing (if that term even applies) is counterbalanced by the mantra-like regularity of his piano; an exposed-nerve of a record that sounds as raw today as it did at the time.

7 James Taylor

Sweet Baby James

(Warner Bros, 1970)

How ironic that this seemingly mellow album is steeped in this fragile artist’s torment in vivid, if allusive, reflections on his struggle to survive in an uncaring universe. Sweet Baby James (the very title suffused in vulnerability) was born out of Taylor’s time in a mental institution, having sought escape in heroin, shattered by the suicide of a friend. The latter experience is poetically recounted in “Fire And Rain” (“Sweet dreams and flying machines in pieces on the ground”), while in the title song he’s daunted by the prospect of going on (“Ten miles behind me and 10,000 more to go”).

8 Loudon Wainwright III

Album I

(Atlantic, 1970)

Although he was just 24 when this debut first appeared, Wainwright was already displaying the sage introspection of an older man that would become a fixture of his music for the next four decades. “In Delaware when I was younger/I would live the life obscene/In the spring I had great hunger/I was Brando, I was Dean,” he sings on the opening “School Days”, while “Hospital Lady” paints a portrait of a sickly pensioner whose only lover is “old daddy death”. The songs are laced with humour, but the dominant tone is one of melancholy, a yearning for places and people left behind (“Ode To A Pittsburgh”, “Central Square Song”), while “Glad To See You’ve Got Religion” envies those happier with their lot (“Me, I’m still in trouble/Sorry, sick and sad”).

9 Kris Kristofferson

Kris Kristofferson

(Monument, 1970)

Kristofferson was into his mid-thirties when he released his first solo album, by which time he was well-versed in the difficulties of making something of himself as a singer-songwriter. The rueful “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” revealed the loneliness and disappointment that he was experiencing in Nashville. Armed with just acoustic guitar, “To Beat The Devil”, ostensibly written for his friend Johnny Cash, also served to highlight his own fear of failure in Music City, while foreshadowing the self-destructive tendencies that would blight Kristofferson’s life throughout the next decade.

10 Joni Mitchell

Blue

(Reprise, 1971)

John Lennon and James Taylor may have bared their souls before her, but Joni Mitchell brought a shimmering splendour to her nervy dissections of love and loss on her fourth album. Amid cascading guitars, Appalachian dulcimers and lilting piano, Mitchell – who described herself as being “vulnerable and naked” during the sessions – holds nothing back on breathtakingly eloquent songs like “Little Green”, reliving the act of giving up her infant daughter for adoption as a desperate 21-year-old (“Child, with a child, pretending”), and “A Case Of You”, in which she throws caution to the winds, knowing how it will end (“Go to him, stay with him if you can/But be prepared to bleed”). The ne plus ultra of confessional singer-songwriter works.

11 David Crosby

If I Could Only Remember My Name

(Atlantic, 1971)

The death of his lover Christine Hinton, who died in a car crash in September 1969, had a profound effect on David Crosby. After CSNY split the following year, he retired to his Sausalito houseboat and, accompanied by friends including Jerry Garcia and Graham Nash, he set about numbing the pain with drink and cocaine and articulating his grief in a set of ravishing folk-jazz songs that often sounded like an extended wake. “Laughing” found its narrator searching for a light to guide him from the darkness. “Traction In The Rain” addressed the difficulty of making it through another day, while “I’d Swear There Was Somebody Here” suggests Hinton’s spirit was always near.

12 Judee Sill

Judee Sill

(Asylum, 1971)

The first signing to David Geffen’s new West Coast label (but overshadowed by the mogul’s other charges, the Eagles and Jackson Browne), Sill was, on paper at least, cut from the same cloth as a fellow female confessor like Joni Mitchell. However, a troubled upbringing, time spent in jail and an ongoing heroin habit arguably informed songs that were starker and less likely to be embraced by mainstream listeners; obliquely autobiographical on “Crayon Angels” and “The Lamb Ran Away With The Crown”, daringly controversial on “Jesus Was A Crossmaker”, depicting the son of God as a sexual predator. The elegance of the musical arrangements and multi-tracking of her voice may suggest the comforting wash of a heavenly choir, but there’s no disguisingthe drama that lay beneath.

13 Nick Drake

Pink Moon

(Island, 1972)

Stricken by the commercial failure of his first two albums, Drake retreated into a depressive shell, recording Pink Moon in two nights in what producer John Wood remembered as a state of monosyllabic despair. The results remain some of the starkest recordings ever made, stripped to the bone to expose a soul in enormous psychological torment. “Place To Be” casts aside a young man’s dreams in place of some ominous future, “darker than the deepest sea”, while on the disturbingly desiccated blues of “Know” the only words are: “Know that I love you/Know I don’t care/Know that I see you/Know I’m not there.” Drake broke down completely following Pink Moon, dying in 1974.

14 Gene Clark

No Other

(Asylum, 1974)

Retreating from Los Angeles and its many disruptive influences, Clark relocated to a Northern California ocean-view cottage, immersing himself in Zen, meditation, nature, family. Though the result, No Other, has been presumed to be submerged in a drug haze, eyewitnesses refute that. The songs, working on multiple planes, spar with Clark’s subconscious on many subjects, including the vast power of music (“Strength Of Strings”) and the cyclical nature of life, death, and creativity (“Silver Raven”), alas alighting on some sobering realisations; as in “The True One” which alludes to his generation’s errors: “They say there’s a price to pay for going out too far.” It all pours forth in the epic introspection of “Some Misunderstanding” — an elegiac appeal for redemption, forgiveness, empathy, transformation.

15 Jackson Browne

Late For The Sky

(Asylum, 1974)

Apparently heartbroken from his affair with Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne’s watershed third album took the poet-songwriter aesthetic into untrammeled, markedly intimate territory. “How long have I been sleeping?” he beseeches of himself in Sky’s title track, while in “Fountain Of Sorrow” he crawls deeply inward, revealing issues of identity, illusion, and romantic confusion (“You’ve known that hollow sound of your own steps in flight,” he sings). Still, for Browne – a newly minted father in 1974 – existential matters deeper than mere romance inform Sky’s most moving numbers: birth, or at least children and the kind of world they will inherit, on the sweeping, apocalyptic “Before The Deluge”; making peace with oneself (the confessional ennui of “The Late Show”); and death – “For A Dancer”, a tribute to fallen friend Scott Runyon that celebrates life’s ephemeral qualities within the sadness.

16 Neil Young

On The Beach

(Reprise, 1974)

Recorded after Tonight’s The Night but released first, this exercise in downbeat self-analysis finds Young wrestling with bittersweet nostalgia, paranoia and depression in the shadow of the Californian sun. While addressing his relationship with the actress Carrie Snodgress (“Motion Pictures”) and alluding to his song-spat with Lynyrd Skynyrd (“Walk On”), he returns again and again to circle the pitfalls of fame. The bleached title track finds him stranded by his predicament (“I need a crowd of people/But I can’t face them day to day”) while the epic “Ambulance Blues” recalls his “old folky days” in Toronto before venting, “All you critics sit alone/You’re no better than me for what you’ve shown.”

17 Bob Dylan

Blood On The Tracks

(Columbia, 1975)

Dylan has often refuted this album’s status as a grand confessional but even his son Jakob admits that “the songs are my parents talking”. The bulk of the tracks form a heartfelt, if opaque, narrative examining his failing marriage to Sara Lowndes from shifting perspectives. “Shelter From The Storm” rewinds to Dylan’s chaotic mid-’60s and his saviour through love, while “Tangled Up In Blue” is an impressionistic précis of the ensuing decade. The rest is all fall-out. The relentless “Idiot Wind” captures the full emotional range experienced when love turns sour, while “You’re A Big Girl Now” and “If You See Her, Say Hello” linger over the whys, whos and wheres.

18 Joan Baez

Diamonds & Rust

(A&M, 1975)

“Yes, I loved you dearly.” Ten years after the demise of their highly public affair, Baez’s best album is haunted by the ghost of her former lover, Bob Dylan. The bittersweet title track – written after Dylan had recited the just-written “Lily, Rosemary & The Jack Of Hearts” down the phone to her – is awash with painful nostalgia, recalling how he “burst on the scene already a legend/The unwashed phenomenon, the original vagabond”. “Winds Of The Old Days” focuses on the “the blue-eyed son” whose “eloquent songs from the good old days…set us a marching… the ’60s are over so set him free.” A cover of “Simple Twist Of Fate” suggests Baez is struggling to heed her own advice.

19 Janis Ian

Between The Lines

(Columbia, 1975)

Janis Ian’s seventh album was a US chart-topper, selling a million copies on the back of its lead single, “At Seventeen”, a timeless and poetic delineation of adolescent angst. However, Ian had already had a big hit single aged 16 (1967’s “Society’s Child”) and been written off as a one-hit wonder, something that plunged her into years of depression. After therapy and premature retirement, Between The Lines saw her move from the political to the personal, with 11 ballads articulating her own personal turmoil. There are meditations on manipulative lovers (“Water Colors”), loveless sex (“The Come On”), and diatribes against a fickle music biz (“Bright Lights And Promises”). Even the jazzy guitars, lavish strings and elegant musicianship of LA’s finest sessionmen can’t sweeten the pill.

20 Paul Simon

Still Crazy After All These Years

(Columbia, 1975)

In the throes of divorcing first wife Peggy Harper, Simon made what he later described as “a whole album about my marriage”. Perhaps the closest he ever came to an intimate singer-songwriter record, its top line traces the contours of a minor mid-life crisis. The McCartney-esque “I Do It For Your Love”, filled with the authentic minutiae of real life, recalls the details of a couple “married on a rainy day” who drift apart. The unsparing truth of “50 Ways To Leave Your Lover” lies in the verses rather than jaunty chorus, while the title track is a portrait of existential ennui.

21 Al Green

The Belle Album

(Hi Records, 1977)

The turning point in Green’s career was arguably three years before this album appeared, when ex-girlfriend Mary Woodson White threw boiling grits over the singer while he sat in the bath, then killed herself with a handgun. He subsequently became less interested in the seductive, sexually charged soul that had made him a star, more enthusiastically pursued gospel music and was ordained as a minister – but The Belle Album, his first without the guiding hand of long-time producer Willie Mitchell, is the sound of a man torn between the saintly and the secular; “It’s you that I want, but it’s Him that I need”, he sings on the title track. Ultimately, religious faith triumphs over sex, Green more determinedly following a righteous path on “Loving You” and “Chariots Of Fire”.

22 Marvin Gaye

Here, My Dear

(Tamla Motown, 1978)

Surely the only album with liner notes written by an attorney, Here, My Dear is a divorce set to music, with all the bitterness, recrimination and sorrow of a 16-year marriage ending. The record is part of the separation, its royalties going, by court order, to Gaye’s ex, Anna Gordy, as part of a $600,000 settlement (Gaye’s fortunes had been squandered, not least on a gargantuan coke habit). Gaye had intended to make a “bad, lazy” album but artistry prevailed, as he obsessively “sang his heart out” on double- and triple-tracked vocals. Meandering and unstructured, Here, My Dear is nonetheless affecting, its allegations of adultery and greed balanced by sadness in songs like “I Met A Little Girl” and “When Did You Stop Loving Me”, while “You Can Leave But It’s Going To Cost You” is a sentiment that echoes through many a divorce.

23 Bryan Ferry

The Bride Stripped Bare

(EG Records, 1978)

Taking its title from the Marcel Duchamp painting The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even, with its subtext of masculine-feminine relationships, Ferry’s fifth solo release was his first since model Jerry Hall left him to take up with Mick Jagger. He picks over the bones of the break-up on the baroque, mournful “When She Walks In The Room” (“All your life you were taught to believe/Then a moment of truth, you’re deceived”) and the country rock of “Can’t Let Go”, and while no stranger to cover versions, the songs of others Ferry opts for here are arguably more pointedly autobiographical, dissections of the end of a romance (The Velvet Underground’s “What Goes On”, Otis Redding’s “That’s How Strong My Love Is”).

24 John Martyn

Grace & Danger

(Island, 1980)

Following the decision of his wife Beverley to finally extricate herself from their ten-year marriage, John Martyn recorded this elegantly anguished confessional. The slick synths, fretless bass burbles and Phil Collins’ jazzy drums cannot temper the emotional clout of the songs here. Following the self-explanatory “Baby Please Come Home”, the pleading “Hurt In Your Heart” and “Save Some (For Me)”, the deceptively soulful “Our Love” makes for an unambiguous kiss-off. Island boss Chris Blackwell delayed its release for a year because he felt it was too depressing. Martyn later called it “direct communication of emotion. I don’t give a damn how sad it makes you feel.”

25 Pete Townshend

Empty Glass

(Atco, 1980)

The few years leading up to Empty Glass had not been kind to Pete Townshend. Keith Moon had died in 1978, while his marriage was failing and he was struggling with alcoholism and drug abuse as well as his commitments with The Who. The result was an album filled with emotional extremes: anger, tenderness and despair chief among them. “I Am An Animal” found Townshend at his most openly confessional, intoning over acoustic guitar lines: “I’m looking back and I can’t see the past/Anymore, so hazy/I’m on a track and I’m travelling so fast/Oh for sure I’m crazy”. The title track, meanwhile, found Townshend examining his own place in a world post-punk: “My life’s a mess, I wait for you to pass/I stand here at the bar, I hold an empty glass”.

26 John Cale

Music For A New Society

(Ze, 1982)

Described by Cale as his most “tormented” work to date, the stark acoustics of Music For A New Society are a direct contrast to the rage of its immediate predecessors. The songs were largely improvised in the studio, a catalogue of laments focussing on damaged souls and misplaced faith (“It was like method acting, madness, there’s not much in the way of comedy,” he told Melody Maker), drawing upon emotional betrayal and disillusionment (“Thoughtless Kind”, “Damn Life”). Cale was simultaneously working on a stage production with playwright Sam Shepard, who provides the lyrics for “If You Were Still Around” (“I’d chew the back of your head/’Til you opened your mouth to this life”), while “Taking Your Life In Your Hands” deals with the cheery subject of a mother on a killing spree.

27 Lou Reed

The Blue Mask

(RCA, 1982)

“I really got a lucky life/My writing, my motorcycle and my wife,” Reed sings on the opening “My House”, raising the curtain on an album that, for the most part, celebrates marriage and domestic bliss, encased in a sleeve designed by his then wife, Sylvia. He continues the theme on the likes of “Average Guy”, “Heavenly Arms” and “Women”, the latter finding Lou even more uncharacteristically upbeat and joyful (“A woman’s love can lift you up, and women can inspire/I feel like buying flowers and hiring a celestial choir”). Musically, the songs are presented in a stripped-down traditional rock’n’roll format of two guitars, bass and drums, with Robert Quine’s eloquent fretwork a perfect foil to Reed’s deadpan vocal and matter-of-fact words.

28 Richard & Linda Thompson

Shoot Out The Lights

(Hannibal, 1982)

Nothing quite conjures up soul searching and bitterness like divorce, and the Thompsons’ final album addresses their break-up with remarkable candour. But it isn’t just the first-hand descriptions of their collapsing marriage that bring such intensity to songs like “Don’t Renege On Our Love”, “Walking On A Wire”, “Did She Jump” and “Shoot Out The Lights” – it’s the fireworks with which Richard and Linda deliver them amid their struggle to keep it together long enough to finish the record: while it was Richard pouring his heart into the songs as the writer, it was Linda who had to sing them.

29 Dexys Midnight Runners

Don’t Stand Me Down

(Mercury Records, 1985)

Once described by Uncut as the band’s “neglected masterpiece”, Don’t Stand Me Down was Kevin Rowland at his most introspective, taking stock of his fame post-“Come On Eileen” and Too-Rye-Ay, and almost wilfully dismantling the constructs of stardom. It’s evident on the two tracks that bookended Side One of the original vinyl release; the anger and petulance of “The Occasional Flicker” and the reflection of times past “Knowledge Of Beauty”. In between those, the song for which the record is best remembered, “This Is What She’s Like”, sneers at middle-class hipsters and bandwagon jumpers, but incorporates a paean to the group’s violinist Helen O’Hara, with whom Rowland had just ended a long relationship, and who was also the inspiration for “Listen To This”.

30 Elvis Costello & The Attractions

Blood & Chocolate

(Demon, 1986)

It’s tough to improve on Costello’s own assessment of Blood & Chocolate: “a pissed-off, 32-year-old divorcee’s version of This Year’s Model.” However, where the angst of This Year’s Model was rooted in the fact that girls wouldn’t talk to him, this album articulated the catastrophe that could ensue when they did. Blood & Chocolate appears to be Costello’s settling of accounts regarding his first marriage, to Mary Burgoyne (though the recently installed second Mrs Costello, former Pogues bassist Caitlin O’Riordan, provided backing vocals on a couple of tracks). “Home Is Anywhere You Hang Your Head” and “I Hope You’re Happy Now” are mournful and furious, while the relentless “I Want You” remains, against formidable competition, Costello’s most lacerating and hostile recorded performance.

31 Bruce Springsteen

Tunnel Of Love

(Columbia, 1987)

If the oddly formal sleeve credit – “Thanks Julie” – told some of the story, the songs on Springsteen’s most nakedly personal record filled in the blanks. With his brief marriage to model Julianne Phillips floundering, he turned inward to tackle, in the words of the title track, “You, me, and all that stuff we’re so scared of.” On “Brilliant Disguise”, he sings “I wanna know if it’s you I don’t trust, because I damn sure don’t trust myself.” On “Walk Like A Man” marriage is a “mystery ride”; on “Two Faces” “our life is just a lie.” And on “One Step Up”, “Another fight and I slam the door on/Another battle in our dirty little war.” Within a year, he and Phillips had filed for divorce.

32 Mark Eitzel

Songs Of Love

(Diablo, 1991)

Stripped of the nuances offered by American Music Club, this solo album, recorded live at London’s Borderline on January 17, 1991, adds up to almost unbearably intimate exploration of Eitzel’s songbook, each page torn from his combustible life in San Francisco. Featuring just Eitzel and his acoustic guitar, the songs touch on the death of friends and family (“Blue And Grey Shirt”), AIDS (“Western Sky”), alcohol and drug abuse (“Outside This Bar”), and, on “Kathleen”, his relationship with a long-term muse. Eitzel’s intense, self-deprecating presence – “I’m always fucking this part up!” he squirms during a guitar break – only adds to the drama.

33 Nick Lowe

The Impossible Bird

(Demon, 1994)

The elegant country, soul and Americana Lowe has mined on his last half-dozen albums began with this release, partly inspired by the end of his five-year relationship with broadcaster Tracey MacLeod, whom he first met when she interviewed him for BBC2’s The Late Show. After the break-up, MacLeod started dating another veteran singer-songwriter, Loudon Wainwright. Lowe chronicles the emotional fallout directly in a triptych of tearjerkers comprising “Lover Don’t Go” (“There’s a hollow in the bed where your body used to be”), “Withered On The Vine” and “14 Days”, although there’s a more upbeat tone to “Drive-Thru Man”, in which he cajoles himself to get a grip on his emotions (“Take a look outside/It wouldn’t kill you to lift that blind”).

34 Steve Earle

I Feel Alright

(E-Squared/Warner Bros, 1996)

Earle spent four months in jail for narcotics offences in 1994, which prompted much soul-searching, not least about his 26-year dependence on heroin. Finally clean, he dusted down his old songbook with the acoustic set Train A Comin’ before tackling his addictions more directly on I Feel Alright. The title track opens the album on a note of defiant optimism (“Be careful what you wish for, friend/Because I’ve been to hell and now I’m back again”) and while Earle’s writing is rarely transparently autobiographical he addresses his situation on “South Nashville Blues” and “CCKMP (Cocaine Can’t Kill My Pain)”. On “The Unrepentant”, our “hellbound” hero addresses the devil directly, with a loaded .44.

35 Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds

The Boatman’s Call

(Mute, 1997)

Cave has acknowledged that The Boatman’s Call is “the setting down of the facts of a couple of relationships… what you hear is what happened.” The relationships in question were with his first wife, Viviane Carneiro, and subsequently with Polly Harvey, who collaborated on his previous album, Murder Ballads. Carneiro is bid a gruff goodbye in “Where Do We Go Now But Nowhere?”, Harvey welcomed with the nakedly descriptive “Green Eyes”, “Black Hair” and “West Country Girl”. Cave has since appeared somewhat sheepish about The Boatman’s Call, as we often do when recalling our own behaviour when the answer to the question “Are You The One That I’ve Been Waiting For?” turns out to be “No”.

36 Elliott Smith

Either/Or

(Kill Rock Stars, 1997)

Smith often drew on personal experiences for his songs – in particular, drug abuse, failed relationships and his own psychological state – but arguably his third record, Either/Or, is the most confessional of his albums. “Between The Bars” addresses the debilitating nature of addiction – “the potential you’ll be that you’ll never see” – while “Alameda” bristles with alienation and defensiveness: “Nobody broke your heart/You broke your own/’Cause you can’t/Finish what you start”. Meanwhile, Smith mines his discomfort with his own growing popularity on “Pictures Of Me”: “Saw you and me on the coin-op TV/Frozen in fear every time we appear”.

37 Paul Westerberg

Suicaine Gratification

(Capitol, 1999)

Kicking off with an ode to mid-life depression (“Get up from a dream and look for rain/Take an amphetamine and a crushed rat’s brain”), the third solo album by The Replacements’ guiding light is an extended essay in anxiety, commercial failure and the after-effects of alcoholism. Partly recorded in his Minneapolis basement, the music and mood is stripped bare. “Self-Defence” contemplates suicide as an escape route, “Sunrise Always Listens” recalls a long dark night of the soul, while “Best Thing That Never Happened” sums up a lifetime of disappointments.

38 Rodney Crowell

The Houston Kid

(Sugar Hill Records, 2001)

Arguably better known to wider audiences through his association with others (long-serving sideman to Emmylou Harris, husband of Johnny Cash’s daughter, Rosanne), The Houston Kid found Crowell telling his own story in a song cycle about growing up in the rough, low-rent east side of the city. “Telephone Road” is vividly descriptive in its portrait of his formative years, difficult circumstances continuing to make their presence felt in the saloon bar twang of “Rock Of My Soul”. The struggles of finding oneself inform “Why Don’t We Talk About It?”, while the bold rewrite of a Cash classic, “I Walk The Line (Revisited)” addresses the hoops he jumped through to impress his father-in-law.

39 Beck

Sea Change

(Geffen, 2002)

Three weeks before his 30th birthday, Beck found out that his girlfriend of nine years, Leigh Limon, had been cheating on him with a member of the LA band Wiskey Biscuit. Beck responded with a dozen pieces of wrecked resignation. “These days I barely get by,” he groans over a sympathetic slide guitar on “The Golden Age”, “I don’t even try.” Beck’s father, David Campbell, provides elegiac string arrangements throughout, but lyrics like “It’s only tears I’m crying/Only you I’m losing/Guess I’m doing fine”, scarcely need much help to tug at the heartstrings. Even Beck’s characteristic studio japery – like the backwards effects on “Lost Cause” – seem reflective of his inner turmoil.

40 Lucinda Williams

World Without Tears

(Lost Highway, 2003)

“Truth is my saviour,” Williams sings on opener “Fruits Of My Labour”, a sentiment that could also double as her manifesto. Always a personal writer, her honesty is at its most immediate on her seventh album, which picks over the bones of her relationship with Ryan Adams’ former bassist Billy Mercer. The live-in-the-studio rawness of the music is more than matched by the words. Tender portraits of a damaged lover (“Sweet Side”, “Righteously”) are weighed against the damage he has caused. If “Over Time”, “Minneapolis” and “Ventura” linger agonisingly over the cooling ashes, on “Those Three Days” the pain and fury is still evident.

41 Warren Zevon

The Wind

(Rykodisc, 2003)

Warren Zevon’s previous couple of albums had been fate-tempting tauntings of the Reaper: Life’ll Kill Ya, My Ride’s Here. Shortly after the release of the latter, Zevon was diagnosed with inoperable mesothelioma; he recorded The Wind knowing he was composing his final testament. He didn’t do so alone: his backing band included Bruce Springsteen, Billy Bob Thornton, Don Henley, Dwight Yoakam, Tom Petty, Emmylou Harris and his songwriter son, Jordan. The Wind lurches across the condemned man’s palette from rueful contemplation of what has been (“Dirty Life & Times”, a lovely cover of “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door”) to defiant determination to enjoy what remains (“Rest Of The Night”, “Keep Me In Your Heart”) to absolute, desolate vulnerability (“Please Stay”). Zevon died two weeks after its release, aged 56.

42 Amy Winehouse

Back To Black

(Island, 2006)

Not even the continuing efforts of countless X Factor wannabes can diminish the potency of Winehouse’s soulful outpourings on one of the 21st Century’s most honest and vulnerable albums. “Rehab” may fit the media shorthand of Amy’s fast life and sad demise, but her love songs are less off-the-cuff and rooted in a deeper hurt. Her stormy on-off relationship with future husband Blake Fielder-Civil and experiences dating others during time away from him informs the emotional safety warning of “You Know I’m No Good”, while “Wake Up Alone” and “Love Is A Losing Game” find her nakedly pining for the man that her heart never let go of. The mellow torch-like balladry recalls sirens from an earlier age (Billie Holiday, Dinah Washington), but few singers have laid bare their diary so powerfully.

43 John Grant

Queen Of Denmark

(Bella Union, 2010)

A unique subversion of ’70s AOR, the solo debut by the ex-Czars singer smuggled personal lyrics beneath a cloak of lush balladry. As darkly funny as they are self-critical, the songs laser through Grant’s doomed love affair with ex-boyfriend Charlie (“It’s Easier”), his memories of smalltown bigotry (“Marz”, “JC Hates Faggots”), and, on the title track, addiction in all its stripes: “When that shit got really really out of hand/I had it all the way up to my hairline.” “My life is in those songs,” said Grant. “I had to throw these things out there.”

44 Josh T Pearson

Last Of the Country Gentlemen

(Mute, 2011)

The Texan son of a preacher was living illegally in Berlin, his career stalled, when the failure of his marriage prompted an emotional and artistic spasm. Before fleeing to Paris, he spent two days in the studio, documenting his torment. The songs are as tough to listen to as they are emotionally honest; the hurt is only partly soothed by the grandiosity of Pearson’s language. He’s vicious to his ex on “Sweetheart, I Ain’t Your Christ”, though he’s just as hard on himself. The process was cathartic: “It really burned something out of me,” Pearson reflected.

45 Sharon Van Etten

Tramp

(Jagjaguwar, 2012)

As a student in Tennessee, New Jersey songwriter Van Etten was trapped in a psychologically abusive relationship, an experience that has permeated her three albums to date. But she only ever reveals awful details to fuel her self-growth, and on Tramp, steeled by raucous production, Van Etten sounds like she’s finally standing upright. “I want my scars to help and heal,” she sings on “All I Can”. “I’m biting my lip as confidence is speaking to me/I loosen my grip from my palm, put it on your knee,” on “Give Out”. It’s a small gesture, but a meaningful one.

46 John Murry

The Graceless Age

(Rubyworks, 2013)

Murry told Uncut that his debut solo album was “certainly autobiographical – perhaps insanely so given our modern aversion to reality and truth.” Central to the story arc is his struggle with heroin, documented on the 10-minute centrepiece, “Little Coloured Balloons”, which details Murry’s near fatal overdose in San Francisco’s Mission District. On this song, and several others (“Things We Lost In The Fire”, “Southern Sky”), The Graceless Age is also an appeal for forgiveness directed at Murry’s estranged wife Lori and their young daughter: “You say this ain’t what I am,” he sings to them both, “but this is what I do.”

47 Alela Diane

About Farewell

(Rusted Blue, 2013)

The fifth album by the Portland-based singer was written in a fortnight, following the realisation that her marriage to guitarist Tom Bevitori was over. Diane refuses to take refuge in metaphor – the language is as clear and stark as the accompaniment, tracing the arc of a relationship from its unromantic beginnings in “Hazel Street”, taking in the snowbound revelation of “Colorado Blue”, the singer with “one foot out the door” on the title track, and the two road musicians marking time in “Before The Leaving”. By the end “Rose & Thorn”, with its cry of “Oh! The mess I’ve made…”, it feels not unlike leafing through a discarded diary.

48 Laura Marling

Once I Was An Eagle

(Rough Trade, 2013)

An artist whose sensibilities cleave remarkably close to Joni Mitchell’s, Marling recorded her fourth album on the cusp of leaving for LA, with a failed love affair trailing in her wake. The result is a dramatic reckoning with past and future, and a character study of Marling and her ex: the “I”, the “eagle”, in the breathless opening suite feels clearly autobiographical, while the “you”, the “dove”, the “freewheeling troubadour”, she is singing to is similarly hewed from real life. Not quite as straightforward as a break-up record, Once I Was An Eagle begins as a full-blooded reliving of a broken-down relationship before coolly addressing the long-term ramifications.

49 ALLISON RUSSELL

The Returner

(Fantasy Records, 2023)

Tracing Russell’s trajectory from early outfits like Birds Of Chicago and Po’ Girl via the Our Native Daughters collaborative project to this, her second solo studio album, the Canadian folk-roots performer emerged as a key artist for 2023 – as well as Joni Mitchell’s favourite clarinet player. Embracing soul, jazz and folk, The Returner explored themes of survival and resilience with grace and power, climaxing with the gloriously uplifting six minute “Requiem”.

50 THE WEATHER STATION

Ignorance

(Fat Possum, 2021)

Tamara Lindeman’s fifth album under The Weather Station grappling with ways to address deeply personal issues while also exploring global concerns – where shimmering breakup songs doubled as a call to arms for the natural world. A song like “Robber” could have been about personal intrusion – a burglary, perhaps, or a metaphor for an emotionally abusive relationship – before revealing itself to be about the dark forces taking control in the name of populism. Such lyrical sweep was not uncommon in Lindeman’s writing. The music itself was full of layered keyboards, subtle electronic shadings, the occasional clarinet or sax, and her own arrangements for a string quartet. Richer textures, but no luxury studio sheen or indulgence: the expanded resources were deployed with the care and rigour that characterised her previous use of humbler tools. In its quiet, wise way, Ignorance was an outstanding piece of work.

Written by Michael Bonner, Rob Hughes, John Lewis, Damien Love, Alastair McKay, Andrew Mueller, Bud Scoppa, Laura Snapes, Neil Spencer, Terry Staunton, Graeme Thomson, Luke Torn

Link to the source article – https://www.uncut.co.uk/features/uncuts-50-best-singer-songwriter-albums-68925/

-

B&C ME60 Studio Subwoofer$94,00 Buy product

-

M-Audio Keystation Mini 32 MK3 – USB MIDI Keyboard Controller with 32 Velocity Sensitive Mini Keys and Recording Software Included,Black$59,00 Buy product

-

Yamaha Wireless MD-BT01 5-PIN DIN MIDI Adapter$54,99 Buy product

-

LP-6 V2 6.5″ Powered Studio Monitor White$199,00 Buy product

-

Novation Launchpad X Grid Controller for Ableton Live$142,99 Buy product

Responses